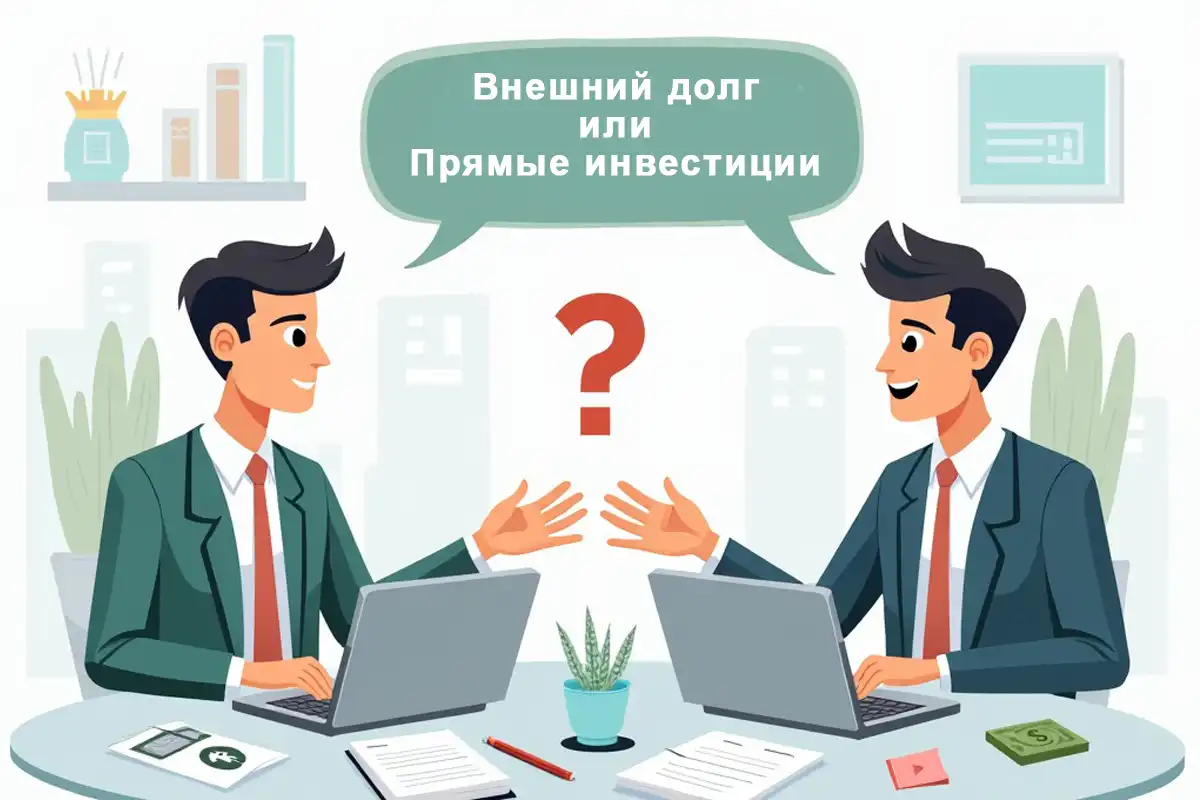

Why is it advantageous for any country to have two units of account (currencies) in its household?

Having two units of account in your country is beneficial, as it reduces dependence on fluctuations in one currency, helps diversify economic risks and simplifies international settlements, especially if one of the currencies is widely accepted in foreign markets.

This paradigm is based on the costs (cost) that the state (organizations, enterprises, individuals) incurs in its national currency (there is only one salary), and receives income mainly from the second unit of account. This is an excellent tool for regulating budget policy for any state.

A bad example is Greece, which once abandoned its monetary unit in favor of only the euro.

A good example is Belarus, which uses two units of account: the Belarusian ruble and the Russian ruble.

Separating the units of account is like having a backup option in case something goes wrong with one of the currencies. For example, if your national currency loses sharply in value, you always have another, more stable currency to buy goods abroad or do business with foreign partners.

When a country uses two units of account at once, it is more protected from crises. As the saying goes, "don't put all your eggs in one basket." Belarus with Russian and Belarusian rubles is just such an example. But in Greece, when they completely abandoned the drachma and switched to the euro, it became more difficult to respond to economic problems, because the tools for managing their currency simply disappeared.

Two currencies are about flexibility, stability, and the ability to insure yourself against unexpected shocks.

So who prevents Greece from exchanging euros for the same dollars or another convertible currency?

Nobody prevents Greece from exchanging euros for dollars or other currencies for foreign trade or savings. But an important point: by abandoning its national currency (drachma) in favor of the euro, Greece lost control over monetary policy. That's the problem.

If a country has its own currency, it can manage its value, for example, reduce its exchange rate to stimulate exports, or print money to cover domestic needs. But Greece cannot do this with the euro. All decisions on the euro (for example, how much money to print or what interest on loans to set) are made by the European Central Bank, which takes into account the interests of the entire eurozone, not just one country.

So currency exchange is one thing, but the ability to manage your economy through your own monetary unit is quite another. Greece once lost this instrument by joining the eurozone. In fact, it now depends on the decisions of others, which complicates the fight against crises.